A study recently published in Nature suggests that an extreme global warming event 56 million years ago known as the Palaeocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) was driven by massive CO2 emissions from volcanoes during the formation of the North Atlantic Ocean. Using a combination of new geochemical measurements and novel global climate modelling, the study revealed that atmospheric CO2 more than doubled in less than 25,000 years during the PETM.

The PETM lasted ~150,000 years and is the most rapid and extreme natural global warming event of the last 66 million years. During the PETM, global temperatures increased by at least 5°C, comparable to temperatures projected in the next century and beyond. While it has long been suggested that the PETM event was caused by the injection of carbon into the ocean and atmosphere, the source and total amount of carbon, as well as the underlying mechanism have thus far remained elusive. The PETM roughly coincided with the formation of massive flood basalts resulting from of a series of eruptions that occurred as Greenland and North America started separating from Europe, thereby creating the North Atlantic Ocean. What was missing is evidence linking the volcanic activity to the carbon release and warming that marks the PETM.

To identify the source of carbon, the authors measured changes in the balance of isotopes of the element boron in ancient sediment-bound marine fossils called foraminifera to generate a new record of ocean pH throughout the PETM. Ocean pH tells us about the amount of carbon absorbed by ancient seawater, but we can get even more information by also considering changes in the isotopes of carbon, which provide information about the carbon source. When forced with these ocean pH and carbon isotope data, a numerical global climate model implicates large-scale volcanism associated with the opening of the North Atlantic as the primary driver of the PETM.

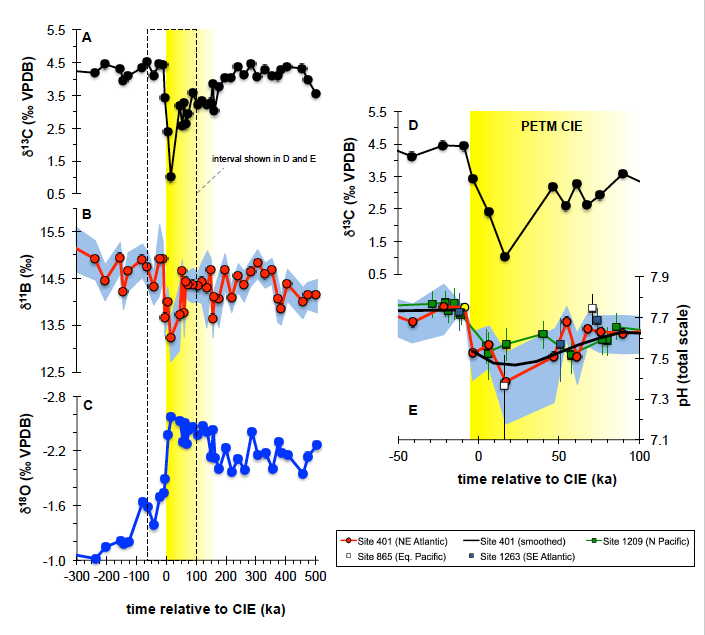

North Atlantic microfossil-derived isotope records from extinct planktonic foraminiferal species M. subbotinae relative to the onset of the PETM carbon isotope excursion (CIE). The negative trend in carbon isotope composition (A) during the carbon emission phase is accompanied by decreasing pH (decreasing δ11B, panel B) and increasing temperature (decreasing δ18O, panel C). Panels D and E zoom in on the PETM CIE, showing microfossil δ13C (D) and δ11B-based pH (E) reconstructions. Also included in E are data from Penman et al. (2014) on their original age model, with recalculated (lab-based) pH values.

These new results suggest that the PETM was associated with a total input of >12,000 petagrams of carbon from a predominantly volcanic source. This is a vast amount of carbon—30 times larger than all of the fossil fuels burned to date and equivalent to all current conventional and unconventional fossil fuel reserves. In the following Earth System Model simulations, it resulted in the concentration of atmospheric CO2 increasing from ~850 parts per million to >2000 ppm. The Earth’s mantle contains more than enough carbon to explain this dramatic rise, and it would have been released as magma poured from volcanic rifts at the Earth’s surface.

How the ancient Earth system responded to this carbon injection at the PETM can tell us a great deal about how it might respond in the future to man-made climate change. Earth’s warming at the PETM was about what we would expect given the CO2 emitted and what we know about the sensitivity of the climate system based on Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports. However, the rate of carbon addition during the PETM was about twenty times slower than today’s human-made carbon emissions.

In the model outputs, carbon cycle feedbacks such as methane release from gas hydrates—once the favoured explanation of the PETM—did not play a major role in driving the event. Additionally, one unexpected result was that enhanced organic matter burial was important in ultimately drawing down the released carbon out of the atmosphere and ocean and thereby accelerating the recovery of the Earth system.

Authors:

Marcus Gutjahr (National Oceanography Centre Southamption, GEOMAR)

Andy Ridgwell (Bristol University, University of California Riverside)

Philip F. Sexton (The Open University, UK)

Eleni Anagnostou (National Oceanography Centre Southamption)

Paul N. Pearson (Cardiff University)

Heiko Pälike (University of Bremen)

Richard D. Norris (Scripps Institution of Oceanography)

Ellen Thomas (Yale University, Wesleyan University)

Gavin L. Foster (National Oceanography Centre Southamption)