Marine microbes are the engines of global biogeochemical cycling in the oceans. They are responsible for approximately half of all photosynthesis on the planet and drive the ‘biological pump’, which transfers organic carbon from the surface to the deep ocean. As such, it is important to determine how marine microbes will adapt and evolve in response to a changing climate in order to understand and predict how the global carbon cycle may change. However, we still lack a mechanistic understanding of how and how fast microorganisms adapt to stressful and changing environments. This is particularly challenging due to the diversity of organisms that live in the ocean and the dynamic nature of the oceans themselves—microbes are at the whim of ocean currents and so get transported large distances fairly quickly. For the first time, a new study published in PNAS provides a prediction on the controls of microbial evolutionary timescales in the oceans. The authors hypothesize that there is a trade-off for marine microbes between ability to evolve to long-term changes versus respond to shorter term variability. Their results suggest that marine microbes commonly experience conditions that favor a short-term strategy at the cost of long-term adaptation. This trade-off determines evolutionary timescales and provides a foundation for understanding distributions of microbial traits and biogeochemistry.

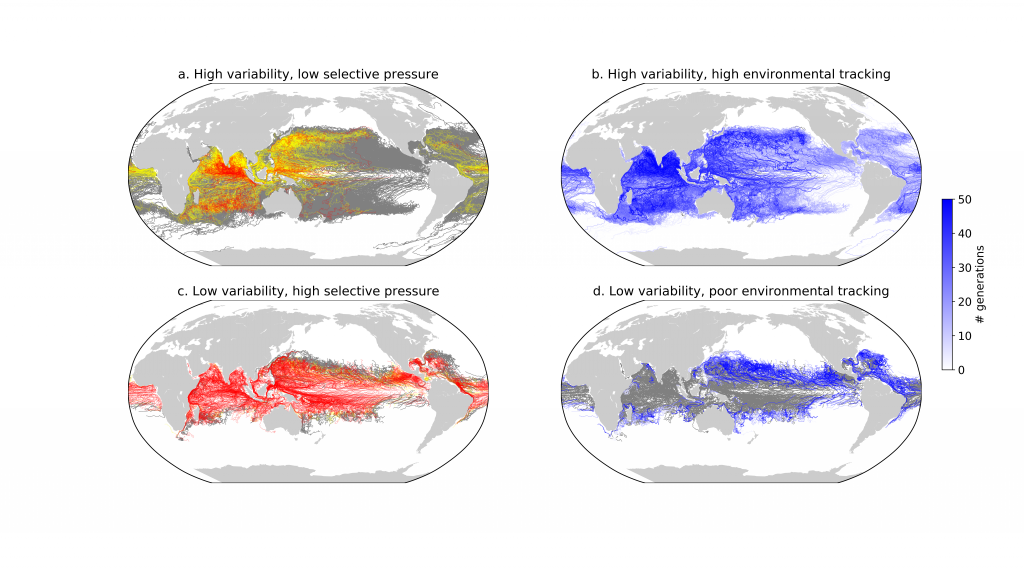

Illustration of trade-off in evolutionary strategy as a function of environmental variability. Trajectories where individuals perceived high environmental variability (a & b) exhibited low selective pressure for any one environment but allowed for high environmental tracking. Trajectories where individuals perceived a more stable environment (c&d) had high selective pressure for ’new environments’ (high probability of a selective sweep) but these individuals exhibited poor environmental tracking. Panels a and c show trajectories where selective sweeps were highly probable (red), likely (yellow), and had a low probability (grey). Panels b and d show the estimated persistence of non-genetic modifications necessary for environmental tracking, where grey indicates unrealistically long timescales.

Authors:

Nathan G. Walworth (University of Southern California)

Emily J. Zakem (University of Southern California)

John P. Dunne (Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory, NOAA)

Sinéad Collins (University of Edinburgh)

Naomi M. Levine (University of Southern California)