The marine chemistry community has measured organic alkalinity in coastal and estuarine waters for over two decades. While the common perception is that any unaccounted alkalinity should enhance seawater buffer capacity, the effects of organic alkalinity on this buffering capacity, and hence the potential CO2 uptake by coastal and estuarine systems are still not well quantified.

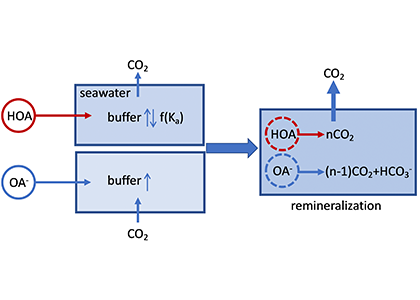

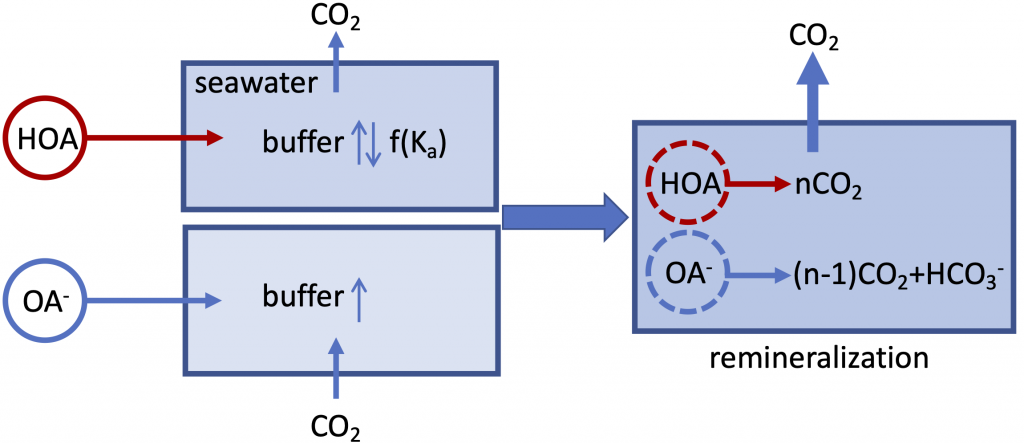

In a thought experiment recently published in Aquatic Geochemistry, the author added organic alkalinity to model seawater (salinity=35, temperature=15˚C, pCO2=400 µatm) in the form of 1) organic acid (HOA) and 2) its conjugate base (OA–). Results suggest that the weaker organic acid/conjugate base pair (pKa ~8.2-8.3) yields the greatest buffering capacity under the simulation conditions. However, the HOA addition first displaces dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) and causes CO2 degassing; the resultant seawater buffer capacity can be greater or less than the original seawater, depending on the pKa. In comparison, OA– addition leads to CO2 uptake and elevated seawater buffer capacity. As the organic anions are remineralized via biogeochemical processes, a “charge transfer” results in quantitative conversion to carbonate alkalinity (CA), which is overpowered by the concomitant CO2 production (∆DIC>∆CA). Overall, the complete process (organic alkalinity addition and remineralization) results in a net CO2 release from seawater, regardless of whether it is added in the form of HOA or OA–.

Figure caption: A schematic illustration of the role of organic alkalinity on seawater carbonate chemistry in an open system (constant CO2 partial pressure). Organic acid (HOA) addition leads to CO2 degassing and varying seawater buffer (greater or lower than the original seawater) as a function of Ka. Organic base (OA–) addition causes initial CO2 uptake and overall elevated seawater buffer. Regardless, upon complete remineralization, more CO2 is produced than the amount of net gain in carbonate alkalinity (OA– addition only). Therefore, the complete process (organic acid/base addition and its ultimate remineralization) should result in net CO2 degassing.

While the presence of organic alkalinity may increase seawater buffer capacity to some extent (depending on the pKa values of the organic acid), CO2 degassing from the seawater, because of both the initial organic acid addition and eventual remineralization of organic molecules, should be the net result. However, modern alkalinity analysis precludes the bases of stronger organic acids (pKa < 4.5). This fraction of “potential” alkalinity, especially from river waters, remains a relevant topic for future alkalinity cycle studies. The potential alkalinity can be converted to bicarbonate through biogeochemical reactions (or charge transfer at face value), although it is unclear how significant this potential alkalinity is in rivers that flow into the ocean.

A backstory

The author used an example of vinegar and limewater (calcium hydroxide solution), which is employed by many aquarists to dose alkalinity and calcium in hard coral saltwater tanks, to demonstrate the conversion of organic base (acetate ion) to bicarbonate and CO2 via complete remineralization. It is also known the added vinegar helps microbes to remove excess nitrate. This procedure had been in the author’s memory for the past nine years, ever since his previous research life when he participated in a study at a coral farm in a suburb of Columbus, Ohio. A strong vinegar odor would arise every now and then at the facility. However, a recent communication with the facility owner suggests that this memory was totally false and the owner simply used vinegar to get rid of lime (CaCO3) buildup in the water pumps. Nonetheless, the chemistry in this paper should still hold, with that false memory serving as the inspiration.

Author:

Xinping Hu (Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi)