It has long been suggested that diatoms, microscopic algae enclosed in silica-shells, developed these structures to defend against predators like copepods, small crustaceans that graze diatoms. Copepods evolved silica-lined teeth presumably to counteract this. But actual evidence for how this predator-prey relationship may drive natural selection and evolutionary change has been lacking.

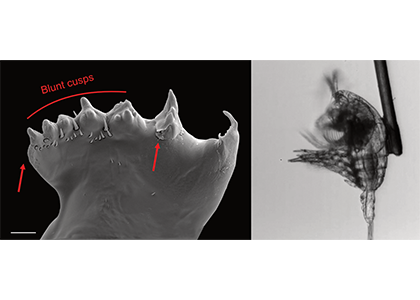

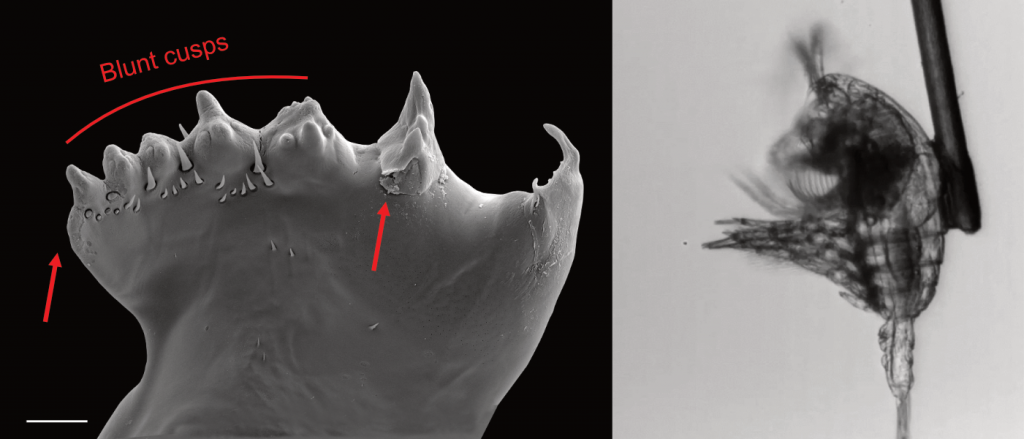

Figure caption: Left: Copepod teeth may suffer damage when feeding on thick-shelled diatoms. The red arrows indicate damage to the copepod tooth, cracks or missing setae. When fed a large diatom, the row of spinose cusps was damaged in all analyzed teeth. Scale bar = 10 µm. Right: A Temora longicornis (ca. 750 µm) copepod tethered to a human hair using super glue, allowing for the capture of high-speed videography to quantify the fraction of cells that eaten or discarded by the copepod. The hair was kindly provided by the first author’s wife.

A recent publication in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U.S.A. revealed a fascinating dynamic: Copepods that feed on diatoms may suffer significant damage to their teeth, causing them to become more selective eaters. The wear and tear on the copepod teeth were particularly pronounced when copepods consumed thick-shelled diatoms compared to “softer” prey like a dinoflagellate. By glueing copepods to human hair and filming them with a high-speed video camera, the authors found that copepods with damaged teeth were more likely to reject diatoms with thick shells than those with thin shells as prey. Shell thickness varies among and within diatom species and some can respond to copepod presence by increasing shell thickness. A thicker shell, however, may come at a cost to the cell in terms of reduced growth rate or increased sinking speed. This suggests that the evolutionary “arms race” between diatoms and copepods plays a crucial role in shaping and sustaining the diversity of these species.

Diatoms and copepods are important organisms in global biogeochemical cycles and hence understanding this microscopic interaction can help predict shifts in marine ecosystems, potentially affecting nutrient cycles and food webs that support fisheries.

Authors

Fredrik Ryderheim (Technical University of Denmark/University of Copenhagen)

Jørgen Olesen (University of Copenhagen)

Thomas Kiørboe (Technical University of Denmark)

Twitter

@fryderheim (Fredrik Ryderheim)

@OlesenCrust (Jørgen Olesen)

@Thomaskiorboe (Thomas Kiørboe)

@OceanLifeCentre (FR, TK group at DTU)

@NHM_Denmark (Natural History Museum of Denmark, JO employer)