Shelled pteropods (pelagic snails) are abundant planktonic predators and prey, linking grazers and higher trophic levels and contributing to the carbon cycle via consumption and excretion. Pteropods have been heralded as bioindicators of ocean acidification, given their aragonitic shell’s susceptibility to dissolution, which could ultimately lead to declining abundance. However, pteropod population dynamics are understudied, particularly in the Southern Ocean, a region predicted to be highly impacted by both warming and ocean acidification. In a recent publication in Limnology and Oceanography, long-term data sets from the Western Antarctic Peninsula show that while there is considerable interannual variability in pteropod abundance, populations have remained stable over the past 25 years, with some pteropod species (gymnosomes (non-shelled pteropod) overall, L. antarctica and C. pyramidata (shelled pteropods) regionally) even increasing during this period (Figure 1).

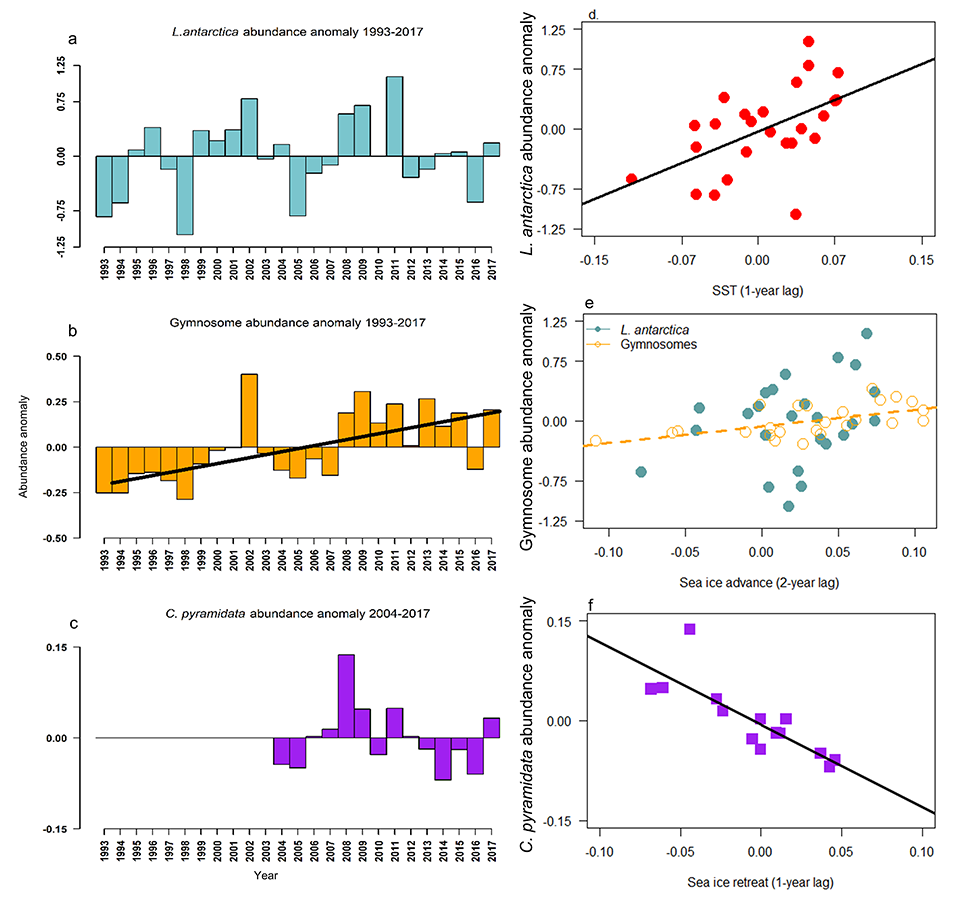

Figure 1. Annual pteropod abundance anomalies for the entire Palmer Antarctica Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) study region along the Western Antarctic Peninsula. (a) Limacina helicina antarctica (shelled pteropod), (b) Gymnosomes – nonshelled pteropods that prey on shelled pteropods (p = 0.007, r2 = 0.27), and (c) Clio pyramidata (shelled pteropod). Effect of environment on pteropod abundance. (d) SST vs. L. antarctica abundance, e) Sea ice advance vs. L. antarctica and Gymnosome abundance, (f) Sea ice retreat vs. C. pyramidata abundance. Data plotted are annual anomalies for each year of the time series (1993–2017). Sea ice advance is lagged 2-yr behind pteropod abundance (e.g., 2017 pteropod annual anomaly is plotted against 2015 sea ice advance annual anomaly) SST are lagged 1-yr behind L. antarctica abundance (e.g., 2017 L. antarctica annual anomaly is plotted against 2016 SST). Regression lines for significant linear relationships are shown, regression statistics are as follows: (d) SST vs. L. antarctica (circles): n = 25, p = 0.006, r2 = 0.25 (e) sea ice advance vs. L. antarctica (filled-circles) and Gymnosomes (empty-circles): n = 25, p = 0.003, r2 = 0.30 (dashed line); (f) sea ice retreat vs. C. pyramidata (squares): n = 14, p = 0.0003, r2 = 0.64.

There was no significant influence of carbonate chemistry parameters (e.g., aragonite saturation state) on pteropod abundance, since the Western Antarctic Peninsula has yet to experience prolonged conditions characteristic of ocean acidification. However, other environmental factors such as warming and associated sea ice retreat were more influential. For example, warmer, ice-free waters in one year typically led to higher pteropod abundances the following year, suggesting that pteropods may be better adapted than expected to warming conditions due to climate change. The authors propose that earlier sea ice retreat promotes recruitment and subsequent expansion of pteropods further South, which could explain their increased abundance in this subregion. These results increase our understanding of pteropod responses to environmental variability, which is important for predicting future effects of climate change on regional carbon cycling and plankton trophic interactions in the Southern Ocean.

Authors:

Patricia S. Thibodeau (VIMS)

Deborah K. Steinberg (VIMS)

Sharon E. Stammerjohn (University of Colorado at Boulder)

Claudine Hauri (University of Alaska Fairbanks)