The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) defines ocean acidification as “a reduction in pH of the ocean over an extended period, typically decades or longer, caused primarily by the uptake of carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere” (Rhein et al., 2013, p. 295). Does this mean that a greater change in pH at the ocean surface relative to the subsurface, or at one location relative to another, always indicates greater acidification? Based on this IPCC definition of ocean acidification, the answer is yes. But does that make sense?

Seawater pH is the negative base 10 logarithm of the seawater’s hydrogen ion concentration ([H+]) and is a useful way to display a wide range of [H+] in a compact form. A change in pH reflects a relative change in [H+]. Thus, anytime we speak of pH changes, we are really referring to a relative change in the chemical species of interest ([H+]). On the other hand, changes in all the other carbonate system variables that we measure are usually absolute. This characteristic of pH can lead to ambiguity in the interpretation and presentation of rates and patterns of change. Improved understanding comes from also studying changes in [H+], which can reveal aspects that studying changes in pH alone may conceal or overemphasize.

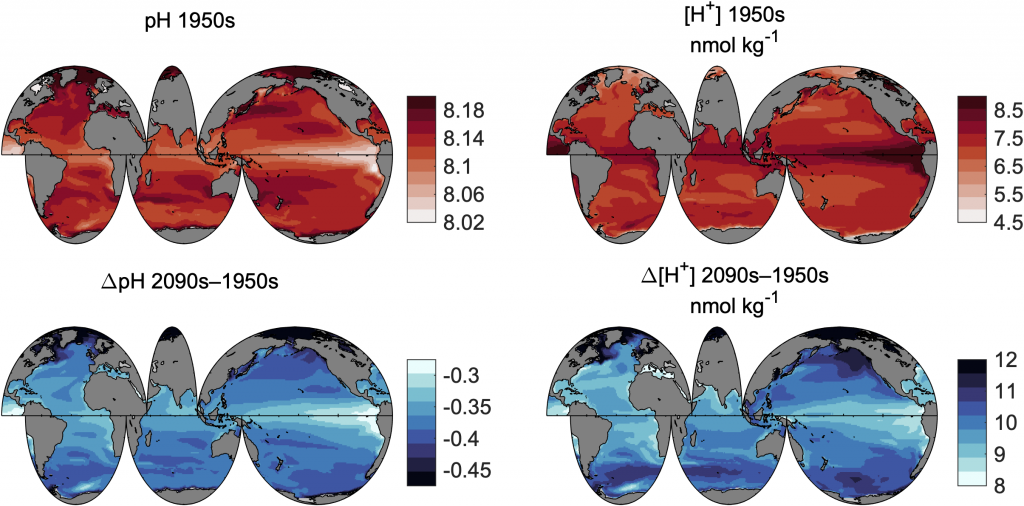

A recent Biogeosciences article reviewed the history leading to this unintuitive relationship between changes in pH and changes in [H+]. The article provides three real-world examples to display how examining pH changes alone can hide the ocean acidification signals of interest (Figure 1). These examples highlight potential challenges associated with comparing surface and subsurface pH changes across ocean domains without accounting for differences in the initial pH values. The authors recommend reporting both pH and [H+] in studies that assess changes in ocean chemistry to improve the clarity of ocean acidification research.

Figure Caption: Data used in this figure come from the GFDL ESM2M model for the combined historical and RCP8.5 experiments. Top: the 1950s surface ocean (left) pH and (right) [H+]. Bottom: the 1950s to 2090s change (Δ) in surface ocean (left) pH and (right) [H+]. The color bar for ΔpH is reversed to ease comparison with patterns of Δ[H+]

Authors:

Andrea J. Fassbender (NOAA Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory)

Andrew G. Dickson (Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California, San Diego)

James C. Orr (LSCE/IPSL, Laboratoire des Sciences du Climat et de l’Environnement)