Timeline

Phase 1 (~ 3 months)

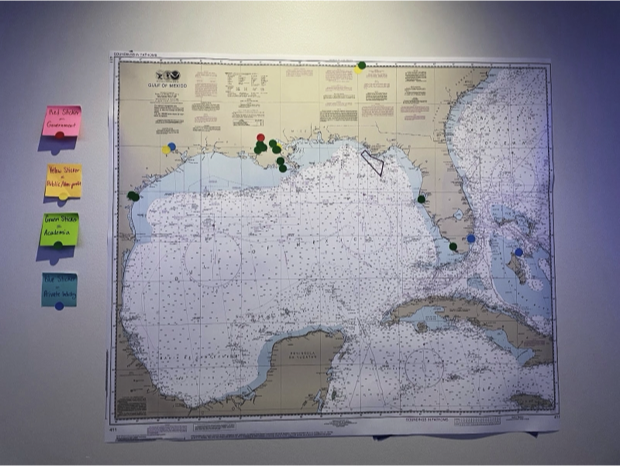

- Establish 6 regional nodes covering Europe, Africa, Asia, North America (via OCB), South America, and Oceania building on and extending the existing global SOLAS network.

- Each regional node will agree on a leader/team of leaders.

Phase 2 (~ 4 months)

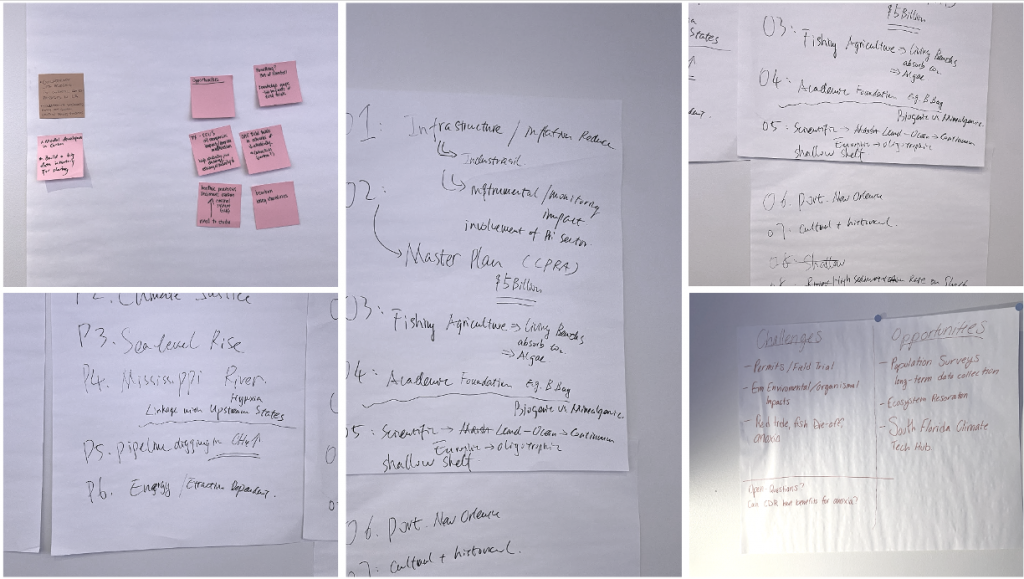

- Each regional node will be working on developing guidelines for monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) for marine CO2 removal.

- After 6 months each node shall submit a summary report addressing the following key questions:

Our goal is reaching consensus on what monitoring, reporting and, verification (MRV) needs to achieve to be considered “satisfactory, yet achievable”.a

Monitoring

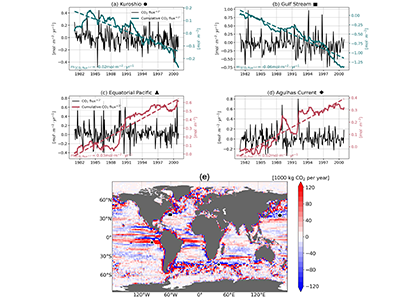

- How far into the future do we have to monitor “removed CO2”?

- Do we have to measure CO2 removal or is modelling acceptable for all (or some) aspects of monitoring marine CDR?

- Should MRV be restricted to CO2 or would other processes affecting radiative forcing (e.g., methane or albedo) need to be essential components of an MRV framework?

Reporting

- How, where, and in what form should data be made available?

- How should we deal with “residual uncertainty”b in MRV frameworks?

Verification

- Who is verifying the data and how?

- Which agency is overseeing the process (e. g. UNFCCC?)

It may not be possible to answer all of these questions satisfactorily. However, attempts to answer them by the continental nodes and their subsequent synthesis will be a first step and help to develop an internationally agreeable MRV framework.

Our synthesis shall be published as “Policy Brief” in a peer-reviewed journal (including all activec participants).

asatisfactory, yet achievable means that MRV should be strict enough to be considered robust, but not too strict so that it becomes impossible to achieve.

bthis refers to uncertainty that potentially exists but currently not quantifiable (e.g. the loss of efficiency in ocean alkalinity enhancement due to biotic calcification).

cactive refers to participants that participate in meetings and engage in the process of answering the questions above in a constructive manner.

Watch the first meeting (timeline, goals, products) of the SOLAS mCDR Global Regional node group.