A recent study by Pohlman et al. published in PNAS showed that ocean waters near the surface of the Arctic Ocean absorbed 2,000 times more carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere than the amount of methane released into the atmosphere from the same waters. The study was conducted near Norway’s Svalbard Islands, which overly numerous seafloor methane seeps.

Methane is a more potent greenhouse gas than CO2, but the removal of CO2 from the atmosphere where the study was conducted more than offset the potential warming effect of the observed methane emissions. During the study, scientists continuously measured the concentrations of methane and CO2 in near-surface waters and in the air just above the ocean surface. The measurements were taken over methane seeps fields at water depths ranging from 260 to 8530 feet (80 to 2600 meters).

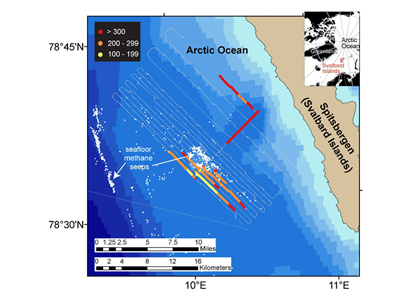

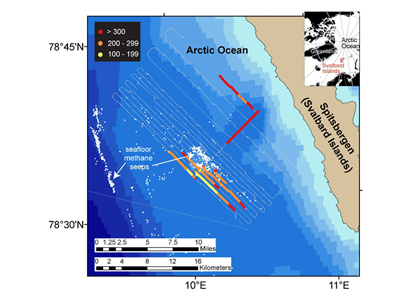

Figure 1. Ocean waters overlying shallow-water methane seeps (white dots) offshore from the Svalbard Islands absorb substantially more atmospheric carbon dioxide than the methane that they emit to the atmosphere. Colors indicate the strength of the negative greenhouse warming potential associated with carbon dioxide influx to these surface waters relative to the positive greenhouse warming potential associated with the methane emissions. Gray shiptracks have background values for the relative greenhouse warming potential.

Analysis of the data confirmed that methane was entering the atmosphere above the shallowest (water depth of 260-295 feet or 80-90 meters) Svalbard margin seeps. The data also showed that significant amounts of CO2 were being absorbed by the waters near the ocean surface, and that the cooling effect resulting from CO2 uptake is up to 230 times greater than the warming effect expected from the methane emitted.

Most previous studies have focused only on the sea-air flux of methane overlying seafloor seep sites and have not accounted for the drawdown of CO2 that could offset some of the atmospheric warming potential of the methane. Phytoplankton appeared to be more active in the near-surface waters overlying the seafloor methane seeps, which would explain why so much carbon dioxide was being absorbed. Physical and biogeochemical measurements of near-surface waters overlying the seafloor methane seeps showed strong evidence of upwelling of cold, nutrient-rich waters from depth, stimulating phytoplankton activity and increasing CO2 drawdown. This study was the first to document this CO2 drawdown mechanism in a methane source region.

“If what we observed near Svalbard occurs more broadly at similar locations around the world, it could mean that methane seeps have a net cooling effect on climate, not a warming effect as we previously thought,” said USGS biogeochemist John Pohlman, the paper’s lead author. “We are looking forward to testing the hypothesis that shallow-water methane seeps are net greenhouse gas sinks in other locations.”

Authors:

John W. Pohlman (USGS Woods Hole Coastal & Marine Science Center)

Jens Greinert (GEOMAR, Univ. of Tromsø, Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research)

Carolyn Ruppel (USGS Woods Hole Coastal & Marine Science Center)

Anna Silyakova (Univ. of Tromsø)

Lisa Vielstädte (GEOMAR)

Michael Casso (USGS Woods Hole Coastal & Marine Science Center)

Jürgen Mienert (Univ. of Tromsø)

Stefan Bünz (Univ. of Tromsø)