When will we see significant changes in the ocean due to climate change? A new study in Nature Climate Change confirms that outcomes tied directly to the escalation of atmospheric carbon dioxide have already emerged in the existing 30-year observational record. These include sea surface warming, acidification, and increases in the rate at which the ocean removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

In contrast, processes tied indirectly to the ramp-up of atmospheric carbon dioxide through the gradual modification of climate and ocean circulation will take longer, from three decades to more than a century. These include changes in upper-ocean mixing, nutrient supply, and the cycling of carbon through marine plants and animals.

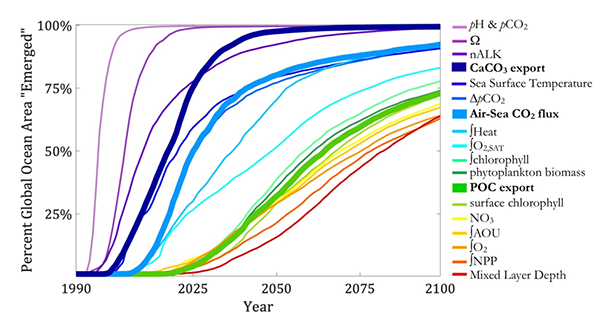

The researchers performed model simulations of potential future climate states that could result from a combination of human-made climate change and random chance (figure 1). These experiments were performed with an Earth System Model, a climate model that has an interactive carbon cycle such that changes in the climate and carbon cycle can be considered in tandem.

Figure 1: Percentage of ocean with emergent anthropogenic trends in ocean biogeochemical and physical variables. A time series of the percentage of the global ocean area with locally emergent anthropogenic trends illustrates the disparity of emergence timescales for anthropogenic changes in the ocean carbon cycle. Emergence is defined as the point in time when the LE’s signal-to-noise ratio for a linear trend referenced to the year 1990 first exceeds a magnitude of two, which represents a 95% confidence in the identification of an anthropogenic trend in the LE Ω applies to the saturation state of both the aragonite and calcite forms of calcium carbonate (CaCO3), for which the emergence times are approximately equivalent. The CaCO3 and soft-tissue pumps were calculated as the export flux at 100 m depth of CaCO3 and particulate organic carbon, respectively. The heat content was calculated as an integral over 0–700 m, whereas the oxygen (O2) inventories consider the integral 200–600 m, and chlorophyll inventories were considered over 0–500 m. NPP represents an integral over 0–100 m. All the other variables represent sea surface properties.

The finding of a 30- to 100-year delay in the emergence of effects suggests that ocean observation programs should be maintained for many decades into the future to effectively monitor the changes occurring in the ocean. The study also indicates that the detectability of some changes in the ocean would benefit from improvements to the current observational sampling strategy. These include looking deeper into the ocean for changes in phytoplankton and capturing changes in both summer and winter ocean-atmosphere exchange of carbon dioxide rather than just the annual mean.

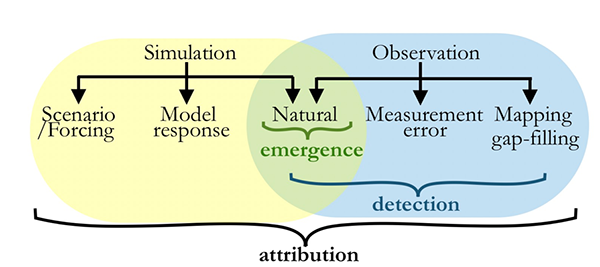

Figure 2. Venn Diagram schematic of sources of uncertainty in simulation (using Earth-System Modeling approach) and observation of changes in the Earth system. For emergence, detection or attribution of an observed or simulated signal to occur, the signal must overcome the sources of uncertainty in their respective brackets.

Many types of observational efforts, including time-series or permanent locations of continuous measurement, as well as regional sampling programs and global remote sensing platforms are critical for understanding our changing planet and improving our capacity to detect change.

Authors:

Sarah Schlunegger (Princeton University)

Keith B. Rodgers (Institute for Basic Science and Busan National University, South Korea)

Jorge L. Sarmiento (Princeton University)

Thomas L. Frölicher (University of Bern)

John P. Dunne (NOAA Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory)

Masao Ishii (Japan Meteorological Agency)

Richard Slater (Princeton University)